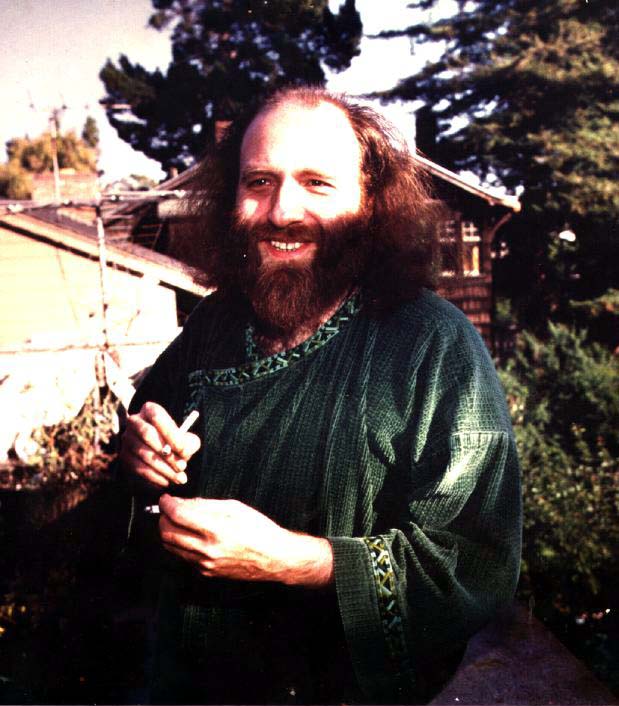

Poet & Swordsman

This Page is Under Very Slow Construction

We are Putting It Up For the Benefit of Paul's Fans

Who Might Like to See a Picture of Him

More Will Follow

As of 26 November 2001, we are way behind on everything. But the estimable Bruce Byfield has volunteered the following article for reprint, for which we are very grateful. We are posting it immediately; we will clean up the formating (our problem, not Bruce's) later. Please read and enjoy it!

*****

Economy of Motion: The Writer's Craft in The Dark Border

by

Bruce Byfield

"It isn't speed," Istvan heard his own voice gasp. "It's minimum motion control--all the things I tried to teach you."

- Paul Edwin Zimmer, "A Swordsman from Carcosa"

Spotting Paul Edwin Zimmer at a convention was easy.

He was the one in a kilt and knee-socks, looking Scottish from his sporran to his skean dhu. You had to squint to find the untraditional touch--five buttons pinned to his jacket. From top to bottom, they read:

The answers to the four questions most frequently asked of Paul Edwin Zimmer:

- Ancient MacAlpin

- Etchings

- No, Marion Zimmer Bradley is not my wife

- There is no third book.

The questions, of course, are:

- What tartan do you wear?

- What's under your kilt?

- Is Marion Zimmer Bradley your wife?

- When is the third book in The Dark Border series coming out?

Instead of repeating himself hoarse, Paul could point to the appropriate answer and not interrupt what he is doing. When there is, say, a discussion about the best translation of Egil Skallagrimson's "Head Ransom," or an alternate version of an old ballad to boom out, who wanted to explain for the seven hundredth time that the MacAlpins were the confederacy of the oldest Scottish clans? Nor is there much point in spelling out that while he was perfectly willing to collaborate on such books as Hunters of the Red Moon, The Survivors, and The Spell Sword, nobody marries a writer who criticized his early efforts at storytelling--even if she isn't his sister.

As for those who still think kilt jokes are witty, the less time spent with them, the better.

Why there is no third book, though, takes space to explain--the space, in fact of the rest of this article.

The simplest answer is that there can be no third book when there was never a series. While The Dark Border exists in two volumes, it has always been a single novel in two volumes. The Lost Prince and King Chondos' Ride are haunting titles, but they were coined for commercial reasons. Quite simply, readers are far less likely to buy a first novel of seven hundred pages than they are two books, each of half the length. So, although Paul wrote about Istvan DiVega in such works as "A Swordsman from Carcosa" and "A Gathering of Heroes," the appearance of an ongoing series is deceiving.

The problem is that fantasy is a commercial genre. Everyone knows how common trilogies and even pentalogies are. They have been around so long that we all know how to pronounce the words. What's more, in buying trilogies and their ilk, we have come to accept certain stylistic traditions.

When King Chondos' Ride ends with: "Then the greatest of living warriors was among them, and his sword was singing," our conditioning tells us that this is the cliffhanger ending we expect from a book midway through a series.

Besides, by the end of the story we want more. We want to see how Chondos rules in his hard-found maturity, and to learn how Istvan finally faces death. Jodos the Lost Prince, too, has such an appalling fascination that his ultimate damnation or redemption seems worth a book or two. Yet those of us who want more must understand that we're unlikely to get what we want, and for the best reason of all.

The Dark Border doesn't need a sequel.

As Istvan DiVega tells a vampire,explaining how his inferior mortal reflexes allow him to kill it, the matter is one of "minimum motion," and the elegant simplicity that comes with control.

Describing a novel of seven hundred thousand words in terms of minimum motion seems a contradiction. It's not, really. With its multiple viewpoints and political intrigue, the novel could sprawl to twice its length. Yet expanding the book would not improve much. Consider, for example, Jodos' thoughts as he is on the verge of his first sexual encounter with a live and willing partner:

The Pure-in-Blood did this, to fatten their victims before they ate them. If he gave her what she wanted, it would make her better eating later, in seven or eight months. By that time, he would be the master here, and his main problem would be to keep this delectable morsel for himself. (Prince 274)

Jodos' thoughts of personal advantage and cannibalism are ludicrous, especially in comparison to the woman's carnality and her desire to carry a royal heir. They could easily be expanded, perhaps satirically.

For Paul, commentary would be especially easy, because Jodos has absorbed Chondos' mind, creating a secondary personality. Chondos' memories debate Jodos' motives elsewhere, so, if Paul had chosen to comment on Jodos' thoughts, he would have had a dramatic means by which to do so already established.

Instead, the secondary personality is kept as a sign of Jodos' stress. Aside from the unnecessary adjective "delectable," his thoughts are left to speak for themselves, in all their matter-of-fact monstrousness. There is no need for explicit comparisons, or for a Lovecraftian excess of adjectives. We laugh at Jodos' thoughts, but our laughter is hysterical, and in the end adds to the horror. The scene is as long as it needs to be, and no longer.

Paul began his career as a poet,experimenting with rigid medieval Welsh forms and the alliterative half-lines of Old Norse years before The Dark Border was published. Turning to prose, he cannot resist a touch of poetry. The ballad of "Pertrap's Ride," whose verses are scattered throughout the novel, is uneven in quality. Some verses have awkward inversion and seem flat. Yet the best verses have power, even when quoted as fragments:

What is that light that gleams afar

Flaming white and gold and red?

Hastur has built him his new tower

And counts us now among the dead.

Or:

He rode into the Twin Sun's light,

And rode up to the tower's door,

And shouted loud at Hastur's gate,

"Men still fight on in Kudrapor!"

Such poetry has no place for extra syllables. Let any creep in, and the lines becomes doggerel. These verses of "Pertrap's Ride," for instance, could be sabotaged by adding a word to each line. For this reason, there is probably no better training than traditional poetry for a writer who cares to learn conciseness.

Paul is not quite so accomplished a prose writer as he is a poet, and a handful of scenes in The Dark Border can be criticized as being mildly over-written. In particular, he could be faulted for the middle, in which scenes of increasingly futile battle follow each other too closely and in too much detail. Yet, in his first solo novel, it is clear that the discipline that Paul learned from verse is also exercised on his prose.

Paul had the knack of tantalizing readers with just enough detail to suggest a fully developed background. In the opening pages, he presents a bewildering list of people and places. Those most important to the story are gradually explained, usually by association rather than by narrative-stopping asides. Yet some of these minor details are never explained fully. For instance, when Miron Hastur descends the Tower of Carcosa, we read that:

He passed by the door that would have lead to the base of the tower upon the moon of Lirdon; he passed the sealed door that once had opened beside the Lake of Hali. (Prince 243)

The moon of Lirdon? The Lake of Hali? Only in "A Gathering of Heroes" do we learn so much as the fact that Lirdon circles the world of the Dark Border. And while the Lake of Hali appears in the works of Robert W. Chambers and H. P. Lovecraft, we know nothing about how it figures into the world of the Dark Border. We know only that the mention of the place adds to the eerieness of the Otherworld where the Hasturs walk at will. And who are the Black Ravens? All we are told is that they are "the elite soldiers of Norbath who patrol the networks of caverns and tunnels that run beneath the Border" (Prince 299), and that they do not rely upon sight in their work--all of which only tantalizes us more. We hardly hear more about the career of Kaljit the Bandit Prince. And what, exactly, are the Zubweth and Dyoles, both Greater and Lesser, that two vampires threaten each other with? The exact pun that Ironfist Arak makes on "Kadar" and "Carrod?" We never do get full answers to such questions.

Naturally, we can speculate. Ironfist's pun is one of the reminders that the world of the Dark Border springs from the same childhood fantasies as Marion Zimmer Bradley's Darkover. In the Darkover books, a "son of Kadarin" is a bastard. Since Ironfist is a half-breed N'Atlantian, and good-natured, can he be calling Martos a bastard like himself? Or, since the Carrodians are famous mercenaries, is Martos being hailed as a fellow mercenary?

We are probably better off not knowing. Too many of the stories in The Simarillion are feeble compared to the mystery invoked by references to them in The Lord of the Rings, and I, for one, would be just as happy if Sherlock Holmes' unrecorded cases had never been the source of pastiches. Once offhand references intrigue us, they have done their work. They let us feel something of the awe that Paul's humans feel for their millennia of history and for the doings of the Hasturs. They invite us to speculate and to make hesitant guesses, and in the movement of our thoughts we create the illusion of a world beyond the confines of the page. When, as in "A Gathering of Heroes," a creature like a Dyole does appear, its terror is all the greater because we do not wholly understand what it is or what it can do. With his careful explanation that the Dark came "from outside the Universe" (Prince 32), Paul has developed his world with a materialism more common to science-fiction than fantasy.

Presumably, he knows more about the world than he tells, and possibly he would like to tell it. Yet the appearance of depth he gives in the phrases and paragraphs that he allows himself could not be improved by a dozen appendices.

One should take time, as well, to examine the transitions between scenes. In a multi-viewpoint novel, each subplot has to be advanced at the right moment without destroying the continuity of the narrative.

The problem is the literary equivalent of juggling with chainsaws: one mistake, and the act fails--messily. In popular literature, Stephen King is probably the master of the necessary slight-of-hand. The Dark Border, though, shows that Paul also has the right reflexes. There is always some continuity among Paul's scenes. One viewpoint character may end a scene by fainting or sleeping while the next viewpoint character begins his scene by waking. Characters may face the same weather under different circumstances, or see a battle from opposite sides--the shortness of the scenes and the frequency of the transitions helps to suggest the confusion of war. Events in Shadow may be contrasted by being followed by a description of the Hasturs' concerns; or two viewpoint characters compared by proximity: Chondos to Jodos, or Istvan to Martos. Paul's shifts in viewpoint are constantly suggesting comparisons, structuring his work on levels of which most readers would be aware only if they were absent. His scenes complement each other, making the novel seem more than the sum of its parts.

The most important of these comparisons begins in the opening scenes. The opening pages of any novel are hectic, but the problems of a multiple viewpoint novel, and a fantasy at that, are greater than most. Characters and situations must be introduced, and entire universes and political systems need to be explained. Paul does most of this routine work in the first three scenes. In their nine pages, he sketches the basic elements of his story: the plot by the Dark Things, the opposition of Light and Dark, and the differences between the Border-folk and the northerners.

He does these things by opening with a panoramic view of the novel's setting. The Dark Border opens in Shadow. It is shortly before nightfall, since the vampire Emicos is stirring and has just fed. The second scene moves north to the opposite side of the Border, with the Twin Suns just setting, and the third shifts northeast to the capital of Tarencia during the last moments of the day. This progress through time and space provides the continuity between what would otherwise be three loosely connected scenes.

At the same time, Paul does something more. In introducing three main characters and allowing a glimpse of a fourth, he begins an implicit comparison among them. The first scene introduces Jodos. Raised in Shadow, "he had never known anything but fear" (Prince 9). Obsessed with avoiding pain, he is self-centered, passive, as he watches the creatures of the Dark prepare their stratagem. By the end of the short scene, he disappears as a person altogether, becoming only a point of view. When the second scene introduces Martos of Onantunga, a young hero in the service f Lord Jagat, a Border prince, at first he seems totally different from Jodos. Gradually, however, a point of comparison becomes noticeable. Homesick, Martos has found himself famous, and he cannot control his pleasure. He is pleased that he is styled as a prince would be at home, and proud to overhear a song about himself. He rebukes himself by quoting philosophy, but soon he is overcome by the memory of his deed. He compromises uneasily with himself:

A good memory to have, whether men praised you for it or not! He could not help it if men praised him, he decided, but he must try to make himself more indifferent to their praise, even should he become as famous as Bithran himself. (Prince 12).

Under some circumstances, the way in which Martos hopes for fame as he stifles his pleasure at the proof of fame could be dismissed as a boyish lack of self-knowledge. Place beside Jodos' egocentrism, it seems disturbingly similar. Both men seem obsessed with themselves, although in different ways.

In the third scene, the viewpoint is Chondos'. Cynical about the flatterers who hound him, wishing desperately that his father would live so he need not become king, Chondos is in many ways as self-absorbed as Jodos or Martos. The difference is that he resents his isolation. He regrets his lack of friends, feeling "poisoned" (Prince 16) by the politics that keep him from trusting those around him. At least part of the reason he dreads his father's death is that his father is the one companion he can trust. That he is capable of finer feelings is suggested at the end of the first scene, as he watches Istvan's arrival. Little is said about the aging man he watches, other than the fact that he is known as "the Archer," yet Chondos' excitement as he identifies him marks the prince's first uncynical moment. Two scenes later, his excitement is shown to be more than incidental; Istvan is a man who keeps his personal integrity while functioning politically, and the dying king has summoned him to be Chondos' role model and advisor.

This transition, from Martos to Chondos to Istvan, is repeated throughout The Dark Border. The movement from Martos to Istvan has continuity, since both men are from the same school of arms, and feel that they should be as father and son. Istvan even speculates that Martos may be himself in an earlier or later incarnation. But what is interesting is how often Chondos' viewpoint is sandwiched between the two others'.

Just under half the scenes in which the viewpoint is Chondos' fall into this pattern, and, in another one-fifth of his scenes, Istvan's or Martos' viewpoint comes both before and after. Nothing is said outright, and the three characters never appear together in the same scene, yet the arrangement of the scenes encourages comparisons. By the time the dying king suggests that Martos would have made a suitable substitute for Istvan to teach Chondos swordplay (Prince 28), we are starting to compare the two heroes.

Before long, we realize that they represent the two extremes that Chondos may grow toward.

Early in the novel, a series of scenes contrast Istvan and Martos. Istvan disguises his meditations about death so well that Chondos, happening across him, sees only the beauty of his sword exercises and nothing of his worries. By contrast, Martos is a stutterer, in as imperfect control of his body as of his mind. He is self-contained, hungry for the praise he knows he would do better to ignore, while Istvan, ashamed of his first heroic act, worries more about others' pain than his own. Waylaid in the street, Istvan tries to avoid battle, then takes a wound himself to put a dying enemy out of pain. In a similar situation, Martos plunges into the fight, watching unconcernedly as a gutted man trips over his own entrails.

The implication of introducing Martos after Jodos soon becomes clear: the differences between Martos and Istvan are a reflection in human terms of the struggle between the Hastur-Lord and the Shadow.

Martos is not evil, yet his weaknesses are uncomfortably close to Jodos' thought-patterns. Like all creatures of Shadow, Jodos hopes that

. . . he might in time grow strong enough to devour Uoght himself, the Great Ones' deputy. Then, when the Great Ones returned, to reclaim the world that had been stolen from them, he would be strong enough to challenge them, perhaps even to eat them all! Then he would be the Survivor, the last being, alone and sufficient unto himself throughout all eternity, hub and centre of the Universe! . . . And even if he could not grow that strong, he must at least grow to make himself strong food for the Survivor. . . Otherwise, the flesh torn slowly from his bones would be eaten by dozens of creatures, goblins and ghouls and trolls, and the Survivor would not remember him at all. (Prince 234)

Just as all the Dark Things hope to be the Survivor, or to be remembered by it, so Martos wishes to be recognized as the finest swordsman of his time, or at least to become famous. At his worst, he sees people and events in terms of how they advance his reputation, communicating poorly even with his lover, Kumari. Aloof amidst his ambitions, he feels no more of a sense of community than the Dark Things do. He contrasts poorly with the Hasturs when the arrangement of the scenes compares him with them (Prince 36-40). as the Hasturs strain to defend the Border, Martos first anticipates lovemaking and then is reluctant to delay it; Kumari has to push him out of bed when the alarm sounds. Istvan, on the other hand, is sick of fame, rejecting the title Martos craves. In his concern for consequences and his refusal to be distracted by his fear of death, Istvan compares much better than Martos does to the Hasturs (Prince 26-36). If Istvan's senses are cruder than the Hasturs', his sense of duty is no less; as a Seynyorean, he has been bred by the Hasturs in their image (Prince 33). During the civil war, Martos is the general intent upon the immediate goals of his campaign. It is Istvan who first foresees a Border without defenders, and Jagat who, recovering from his grief for his son, sends Martos to propose a truce.

While the two heroes command opposing armies, Chondos struggles to escape confinement in Shadow. His struggles broadly parallel the fortunes of the armies warring in his kingdom across the Border. As the various factions scramble for advantage, Chondos plans his first escape. His motives are suggested by the words from "Pertrap's Ride," he recalls as he prepares:

You will but die upon the road

While cold your undead corpse returns. (Prince 303)

Spoken by the legendary hero's fellows, the lines say nothing about duty. They are defeatist, an appeal to self- preservation, and it is in this spirit that Chondos nerves himself to flee. Yet personal safety is not enough of a motive, and, as Martos' guerilla tactics harass Istvan, Chondos is recaptured by goblins. The war settles into a stalemate, advancing Jodos' plan to destroy the kingdom, and Chondos is dragged back to his prison. There, he is befuddled by torture and vampires (possibly the most suitable representatives of the Dark, since they are careless about how their immediate gratification may affect the long-term plans of the Shadow). It is while Istvan and Jagat discuss peace that he starts to struggle for control of his mind. The truce is settled when Chondos overhears Jodos' plans. Kingship stirs in him "like a prodded lion" (Ride 332), and his sense of responsibility motivates him as the urge for self-preservation could not; he recalls the mindlock Miron Hastur taught him, rushes his captors, and escapes. On the way, he is sustained by other fragments of the ballad: Pertrap's ride to save his Dark-surrounded troops provides a comforting parallel to his own race to save his subjects. Fending off vampires and goblins, he staggers across the Border just in time to meet Martos' patrol, which is riding the Border as part of the newly-made truce.

By the time he meets Martos, Chondos is a changed man.

Where he once used his sword awkwardly, over-eager for Istvan's praise, Chondos fights his pursuers with a skill that Martos admires. Self-absorbed before his abduction, after his escape he is mainly concerned with thwarting his evil twin Jodos:

". . .or"--The young man straightened, and lowered his point to the ground--"if you are so sure that you must kill me, at least ride to the Hasturs afterwards, and let them examine the man who calls himself king of Tarencia! And stop that meeting! (Ride 396)

Watching him, Martos pays tribute to Chondos' new determination and sense of responsibility, admitting in his thoughts that "That is a king" (Ride 400). Returning the scrutiny, Chondos sees, not an equal or a model, but a useful lieutenant. Although he resembles Martos at the novel's start, at the climax Chondos has moved beyond him. The change is reflected in the shifts of view: while Chondos' viewpoint is often placed between Martos' in the first half of the novel, in the second half it is more apt to be between Istvan's.

To an extent, Martos matures with Chondos. He controls his stutter at a crucial point, and, standing at a mass funeral after the truce, he realizes the senselessness of the war he has just fought. He commits himself to an obscure life on the Border with Kumari, experiencing a sense of community as a funeral chorus is chanted and he watches "a single tremendous bonfire in which friend and foe, Borderman and mercenary, were one" (Ride 364). He becomes less useful as a contrast to Chondos, and, to judge by the shift in viewpoints, tends to be replaced as the negative model by Jodos. So far as his original purpose goes, in the last few chapters Martos could be forgotten.

However, Paul was not so wasteful. After a few victories over his weaknesses, Martos is killed at the climax by the re-emergence of his conceit. Earlier, fighting the giant Arak Ironfist, Martos senses victory. "Ironfist was no match for him," he thinks, "and the Carrodian, too must know" (Prince 292). After all, Martos reasons, he has defeated Arak in sword-practice. Belatedly, he realizes that "Ironfist's reputation had not been made with a sword but with the axe," and falls, battered unconscious.

After this scene, Martos' thoughts as he fights Istvan are decidedly ominous.

Istvan has just accepted the fact of death, and Martos cannot loosen his tongue to explain that their fight is unnecessary. He becomes caught in the thrill of battle:

He could kill this man; he knew it now. He moved in like a whirlwind, his heavier blade hurling back the other like straw, forcing the fragile figure to give ground before him. He saw the counter-attack he had expected and pounced, his blade leaping up for the two-handed blow that would make him, beyond all doubt, the greatest living swordsman.

And saw, too late, the terrible,inescapable response.

(Ride 409-10).

The final irony is that each man defends what is foreign to him. It is Martos who fights for the matured Chondos, and Istvan who unknowingly defends the Lost Prince Jodos. In fact, had Martos not been so impressed by Chondos' urgency that he discarded his armor, lightening his horse's load so that he could do his duty and deliver his warning in time, his wound might not have been fatal. As it is, Martos dies because he is tempted by his weakness. He delivers his warning only when he is dying and fame no longer matters. Instead of being discarded, he is transformed into a tragic figure who battles his weakness until he is overcome by his struggle.

After such an economical structure, it should have been obvious that Paul would not give us a cliffhanger ending. The control that governs the rest of the novel, structuring it and enriching its characterization, does not disappear in the final paragraph. In fact, the final pages are actually the model for the rest. "I wrote the ending first," Paul once wrote to me, "after reading 'The Defense of Guenevre.' The book was written to lead to the ending."

Paul refers to the poem by William Morris, an Arthurian piece that might surprise those who think of the Pre-Raphaelites as being full of lilies and languor and vice. Written in terza rima, with a minimum of archaicism and inverted syntax, "The Defense of Guenevre" is itself a fine example of poetic economy. In Morris' hands, Guenevre's defense against charges of adultery have a taut simplicity, particularly in the repeated line, "God knows I speak the truth, saying that you lie."

More to the point, the poem ends with Arthur's courtiers straining to hear an approaching sound:

Her cheeks grew crimson, as the headlong speed

Of the roan charger drew all men to see

The knight who came was Launcelot in good need.

The deliberate understatement is stronger than any melodrama. Nor is anything more needed. Aside from the fact that Morris could count on his Victorian readers to know that Guenevre would be rescued, the arrival of a champion is enough to complete the poem. In her defense, Guenevre complains that she is unfairly damned because she was given a choice between two mighty lovers. Put on trial by one of those lovers, she is in despair. The coming of Launcelot, the second one, gives her hope.

Not only is Paul's ending in keeping with his economy throughout, but it is all that is needed. Jodos is obviously not going to carry out his plan. The Shadow obviously will not advance, nor will Chondos be mistaken for Jodos again. As for Istvan's final attack on the cowering Pure-in-Blood, is there a doubt about who will win? His sword is singing, and the slaughter of the men of the Dark has started. No denouement is needed, much less a sequel. Zimmer ends with the climax with all his plot-lines resolved. He loses nothing by doing so, and gains immensely in economy of motion.

Paul never did return to the country of The Dark Border again, although he toyed with a story about Jodos finding refuge in a trading town. But, if he had, we can be sure that there would have been a new set of concerns, rather than a replay of the old ones. All that is necessary to say had already been said.

Appendix A: A Dark Border Chronology

These stories were written in reverse order. Paul had many of the details about his world and characters planned for years. Some, in fact, were sketched out in his teens and have been elaborated on since.

1. Ingulf the Mad: the origin story for Ingulf.

2. A Gathering of Heroes: Between Ingulf's visit to the city of the Sea-Elves at the start of Ingulf and the defense of Rath Tintallain in Gathering, he raided into Sarlow in a lengthy campaign,which has gained some fame. Presumably, then, this novel takes place at least a year after Ingulf. Ingulf's story is summarized (110).

Istvan DiVega seems in his physical prime. He is not worried about aging, and is in less perfect control of himself than later. He still feels pride in his reputation, and at least once he loses control of his reflexes. He has commanded his mercenary company "for many years" (115), but only had larger commands now and then. His son Rafaeyl is off adventuring for the first time. All evidence suggests that Istvan is somewhere between 40 and 50.

3. "A Swordsman from Carcosa" (Fantasy Book, March and June 1986): Istvan's son Rafaeyl is dead, recently enough that he still mourns and has fatherly feelings towards Rafaeyl's best friend Aimon. He has intimations of age when he is wounded and reflects that "a knock on the head was no joke at his age," but is still fit, which suggests that he between 55 and 60.

4. The Dark Border: Istvan's son is dead "eight years" (The Lost Prince 285). He is haunted by fears of aging, and sick of his fame. He recalls events of A Gathering of Heroes abruptly, as if he has not thought of them for a long time (The Lost Prince 265). Since "to his own eyes, his body still looked young" (The Lost Prince 123), but his endurance diminishes on long marches, he seems somewhere between 60 and 65.

Istvan also mentions the search for the stolen infant Jodos as happening almost twenty years ago, which places the event a few years before or after A Gathering of Heroes. The search is Istvan's second visit to Tarencia, the first occurring when he is trying to extend his reputation between the ages of 17 and 22.

References

Zimmer, Paul Edwin. The Lost Prince. New York:

Playboy Paperbacks, 1982.

--------. King Chondos' Ride. New York: Playboy

Paperbacks, 1982.

---Bruce Byfield

*****

*****

If you are missing some of Paul's books and want them immediately, try following this link to Our Own Little Bookstore. (Can't swear they will be there as yet, but when we get this worked on...)We would appreciate the extra income.

If you would like to explore the output of some other writers, try following this link back to the Literary Bragging page, where you may find links to pages about other writers, as soon as they can be prepared.